12 Ways to Dramatically Improve your Research Manuscript Title and Abstract

by Katharine Martin

by Katharine Martin

The first thing a person doing literary research will see is a research publication title. After that, it’s the abstract. These are the first tools that help the reader decide if this journal article is going to help them find what they're looking for or not.

In this article, we provide 12 tips that will help you come up with a concise, straightforward and very accessible title and abstract for your research publication.

Titles are hard to come up with. Thankfully, there are processes, formulas, characteristics and other tips to help scientists in particular devise the perfect title for their work.

Giving your title careful thought and consideration makes all the time spent researching worth it. These title tips have been curated from NCBI along with other journalistic editing services.

After the mental exhaustion of hands-on research, literary research, and finally writing a paper, there is no more energy for the creativity required for title creation. Having a protocol to follow, can absolutely save you time and frustration.

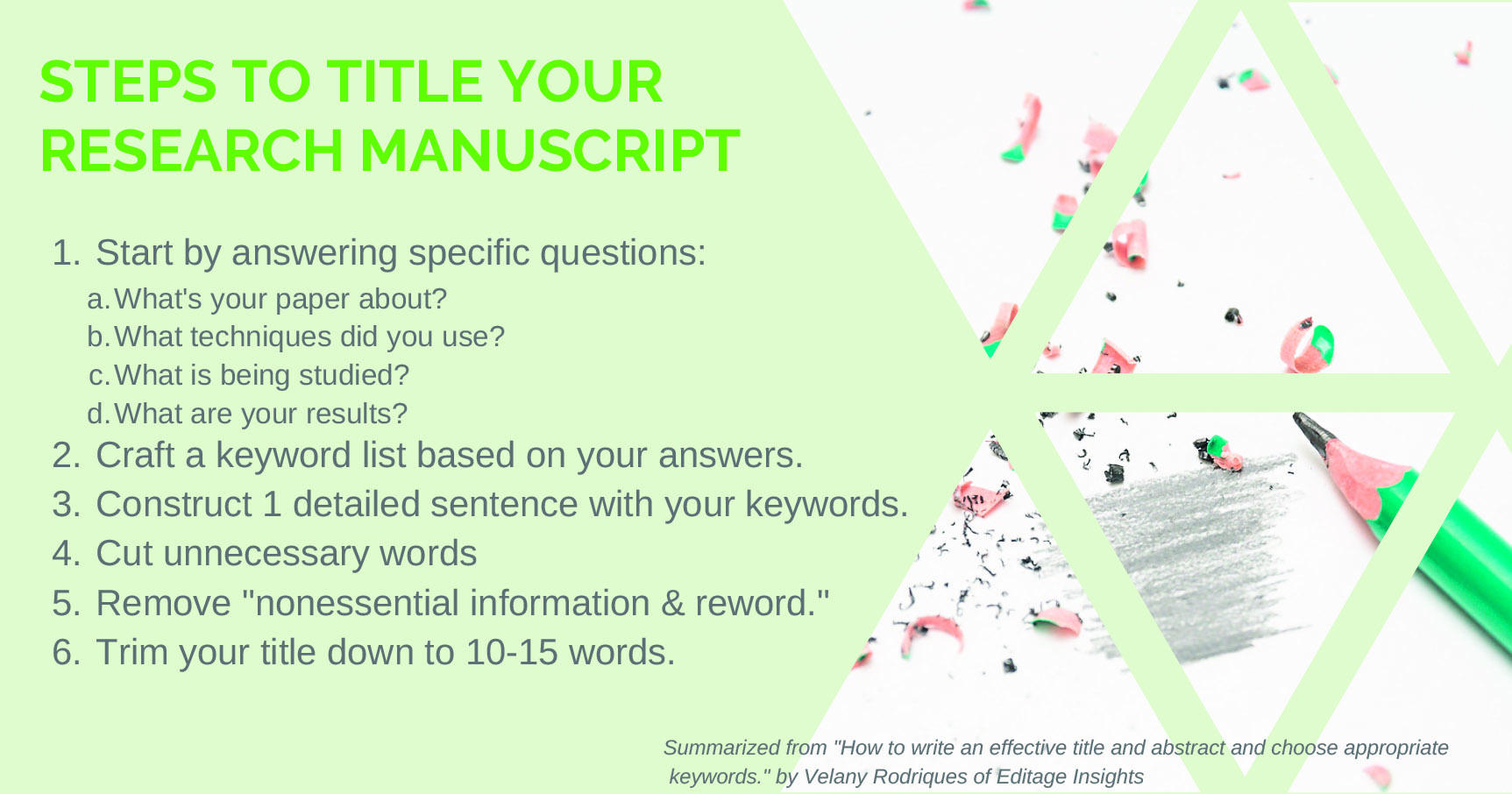

This guide is proposed by BLES (board of editors in the life sciences) certified editor Velany Rodrigues details an easy way to approach title creation. Here is the summarization:

Rodrigues’ article goes into more

detail about this stepwise approach and provides valuable examples for extra

help.

While a process approach can be really helpful, it can take some time and leave you very dependent on one way. However, examining the characteristics of what makes up a good title, can help speed up the process, or at least help you understand the why behind the approach.

Enago Academy, which is an organization dedicated to helping researchers through the publication process, details four key elements that make up a good title:

Sometimes, a template is the best

way to go. You’re tired, you can’t think anymore. There’s no more time left,

and the title is the last thing you want to put effort into, even though you

know you should.

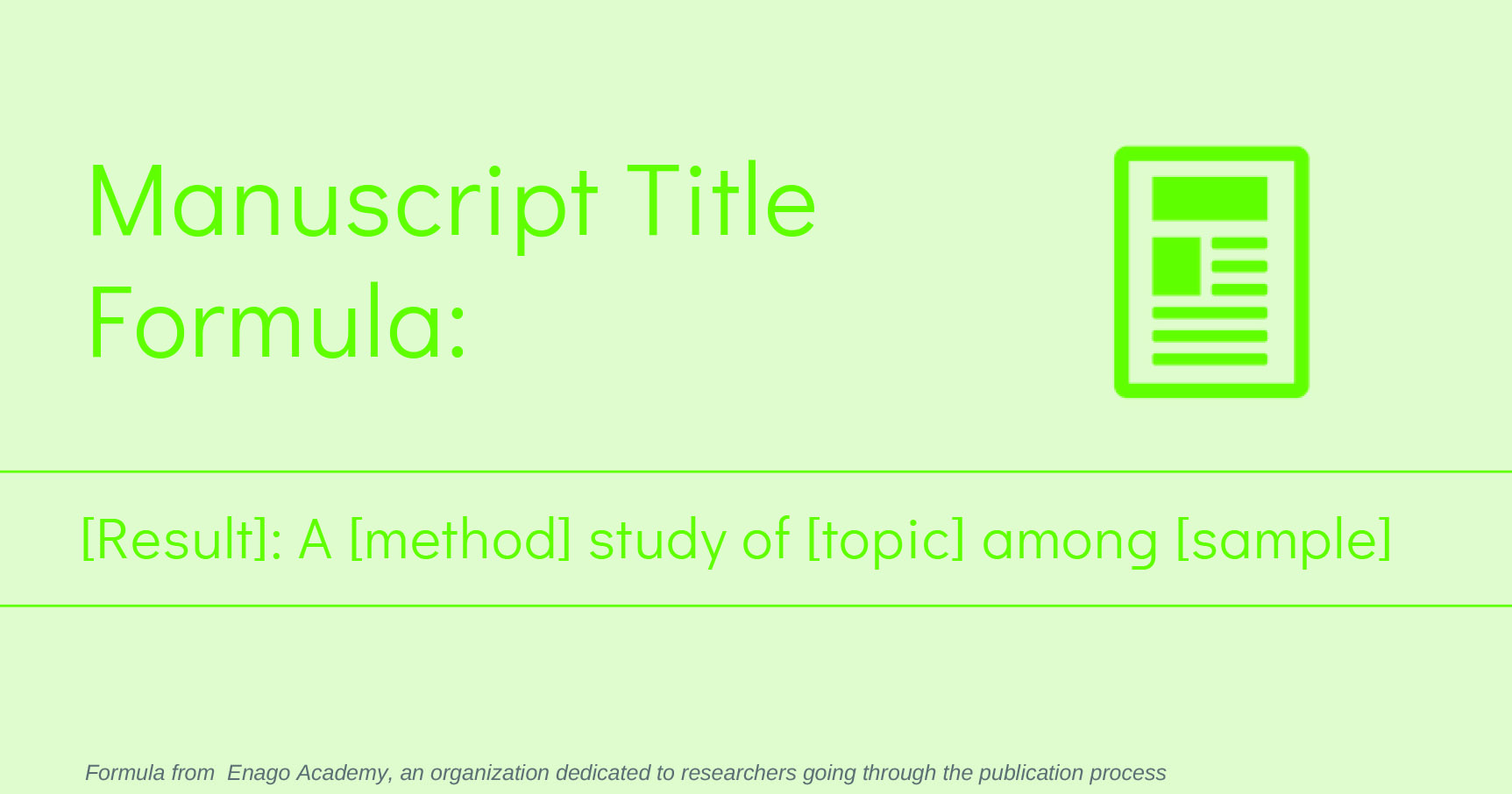

Consider using Enago Academy’s

formula for scientific title creation. Using this formula will require you to

consider title characteristics in part 2, but it reduces the thought work.

Enago Academy Formula:

[Result]: A [method] study of

[topic] among [sample]

Example: “Meditation makes nurses perform better: a qualitative study of mindfulness meditation among German nursing students” (15 words)

Before you rely heavily on a formula, however, make sure you review the characteristics and ask yourself it if checks those off. Furthermore, be certain your title stays between 10-15 words.

By naming the organism, species or material your research is about immediately in the title, you help your audience discover your paper.

Not only is it important to mention the organism in the title, it’s important to put that early in the title to optimize search.

Most of us conduct our literary research online, and one of the early lessons of search engine optimization (SEO) is syntax. Search engines historically deemed a content piece more relevant to the searcher when the keyword is placed earlier in the sentence (title in this case).

Most every article online about title construction for scientific papers will all agree: do not use abbreviations and jargon in the titles.

Naturally, jargon is going to be a little harder to avoid. There is no other way to say Saccharomyces cerevisiae or S. cerevisiae that would be scientifically acceptable in the title of a research paper. But you should always look for an opportunity to simplify terms into more common words or keywords whenever possible.

Most advice articles agree to keeping titles between 10 - 15 words. Some even go as far as saying a title should be no longer than 30 characters. The character count can be tricky depending on the name of your organisms, or methods used. Reduce the character count whenever you can, but it’s more important to focus on word count.

That is not to say this is a hard rule. There are times when your title is going to hit 20 words and there is nothing more you can eliminate. If you’ve already made an effort, and have cut your title down as far as you can while maintaining the important information, then you’re all set.

Punctuation can help set tone. Poor usage of punctuation can over or underinflate the expectations of an article. It can also influence a reader’s perception of a paper. When punctuating your title, make sure to be grammatically correct. Colons and commas can add to a title, making them easier to understand. However question marks and exclamation marks should always be avoided in academia.

Sometimes you just can’t help it. There’s a pun dying to be used for a title, or there is a play on words that is so perfect. Don’t fall for this temptation. Using humor can take away from the overall tone and professionalism of your manuscript. It can also lead to rejection.

There are rare times when a clever or humorous title contributes to your paper. Daniel Oppenheimer’s “Consequences of Euridte Vernacular Utilized Irrespective of Necessity: Problems with Using Long Words Needlessly,” is one example. The publication earned him an the Ig Nobel Prize in literature (the Ig Nobel Prize “honors achievements that make people LAUGH, then THINK.”)

BLES (board of editors in the life sciences) certified editor Velany Rodrigues’ article “How to write an effective title and abstract and choose appropriate keywords” details the different types of abstracts, how they’re structured and the types of publications they’re used for. This information is helpful because it helps a writer further determine the goals of their abstract. And having clear goals leads to better structure.

There are three types of abstracts:

Descriptive abstracts, Rodrigues explains, mostly appear in the social sciences. These abstracts won’t include information about the methods used or the results found.

Informative abstracts are used in the hard sciences. These abstracts detail the purpose, methods, results and conclusion of the study.

Structured abstracts are the same as informative abstracts. However, structured abstracts are broken down into a series of topics that sample the paper’s primary topics. A structured abstract will usually contain a section for objectives, methods, results and conclusion.

More than likely, your paper’s abstract (assuming the readers of this article are life scientists or chemists) will be an informative abstract.

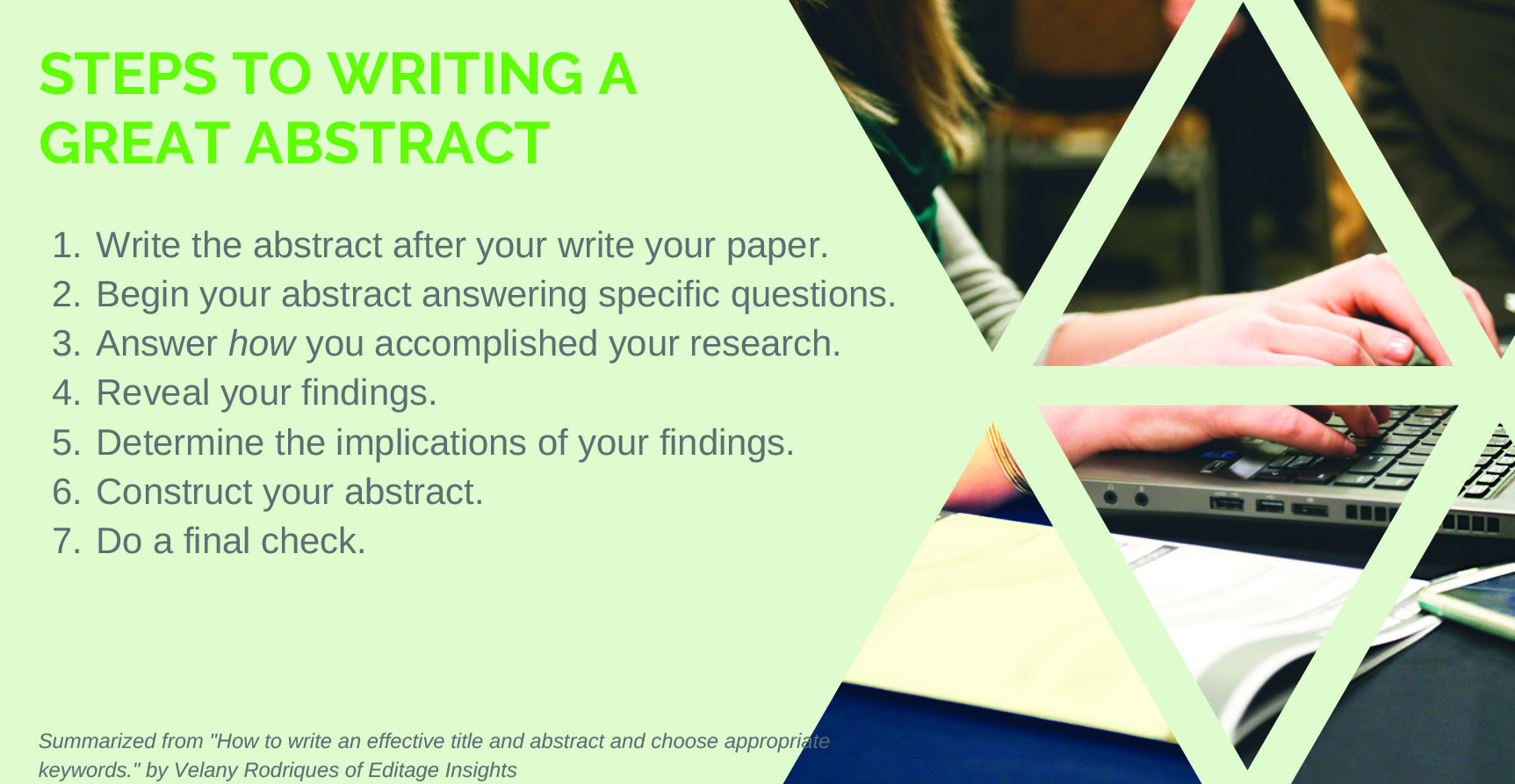

Rodrigues put together a helpful stepwise process for developing straightforward abstracts:

This advice has always been used for title construction. But since the abstract summarizes your research, the same technique applies. Once you have finished your paper, you deeply understand the results, methods, impacts and conclusions of your research.

Rodrigues says to answer these questions by looking to three of your major objectives or hypotheses and your conclusion from the introduction and conclusion section of your paper.

To determine how you accomplished your goal, review the methods section of your paper and choose the most important sentences.

Review your results section. What were the major findings? Make note of these findings as you prepare your abstract.

From your conclusion, what inferences did you make? What were the primary consequences, effects or associations made from your research. Identify these sentences to help prepare your abstract.

You now have all the information needed to properly summarize your work. Take this information and arrange it in order of introduction, methods, results and conclusion. Take some time to rewrite the paragraph so that it is concise and easy to understand. Review it to make sure it addresses questions you anticipate a researcher asking.

It is common with newer researchers to hide the conclusions and impact, making the reader search for it. The “great mystery story,” as Jerold L. Zimmerman puts it in his article about improving manuscripts, forces the reader to struggle to find the answers they need. But doing this could get your paper passed up entirely by editors and readers. It’s imperative you put your purpose, findings, results and conclusion up front.

Do not be afraid of spoiling your paper. Making this information clear right away motivates your reader to keep going and ultimately leads to overall readability.

The audience of a scientific manuscript is going to be broader than most people realize. Typically a writer, especially a newer one, will make the mistake of writing at a higher level than necessary, excluding a large potential audience.

“A paper’s impact is greater if it is written for the largest possible audience…” Zimmerman writes.

The audience comprises people in your niche, of course, but also includes people of different research levels. Undergraduate and graduate students, for example might look at your paper. Due to the interdisciplinary nature of science, potential collaborators outside of your discipline might also stumble across your abstract.

Scientific journalists are another potential audience. And then there are curious intellectuals who do not have a scientific background but do fact-check and might find your abstract.

Furthermore, there is one more very important audience member to consider when writing your abstract: Google (and online search).

Considering that the largest audience can come from all directions, and may not even be human, Zimmerman advises manuscripts and abstracts be written for the least sophisticated of your potential audience.

AJE. (n.d.). Choosing a Catchy Title for Your Scientific Manuscript. Retrieved February 19, 2020, from https://www.aje.com/arc/choosing-catchy-title-your...

Bowman, D., & Kinnan, S. (2018). Creating effective titles for your scientific publications. VideoGIE, 3(9), 260.

Ishtee, Kutton, M., Zubair, Gripo, J., Nahfizah, Rapotra, S., … Feline. (2019, December 5). 4 Important Tips On Choosing a Research Paper Title. Retrieved February 19, 2020, from https://www.enago.com/academy/write-irresistible-research-paper-title/

Rodrigues, V. (2013). How to write an effective title and abstract and choose appropriate keywords. Editage Insights (04-11-2013).

UCI Libraries. (2019, September). Writing a Scientific Paper: TITLE. Retrieved February 19, 2020, from https://guides.lib.uci.edu/c.php?g=334338&p=2249904

Zimmerman, J. L. (1989). Improving a Manuscript's Readability and Likelihood of Publication. Issues in Accounting Education, 4(2), 458–466. Retrieved from http://gent.uab.cat/diego_prior/sites/gent.uab.cat...

Handles are common in everyday life. We use them to help us open doors, cabinets, or to hold coffee mugs, cookware, and tools. They are...

Labeling antibodies with biotin or a fluorophore enables scientists to detect, track, and quantify that antibody and the molecules that it binds to. We cover...

Covalently conjugating a small molecule to an antibody’s surface is a process called antibody “labeling.” Labeling antibodies with small molecules such as biotin or fluorophores...

DNA gel electrophoresis is one of the most widely used analytical techniques in molecular biology, providing a simple and reliable way to separate DNA fragments...